Common PDF errors or mistakes

PDF files are used to send print-ready data to printers. The file format is also frequently used for submitting adverts to publishers or as a graphic file format for logos and drawings. Even though the file format itself is reliable, PDF files can still be troublesome.

Common PDF errors or mistakes

In 2017 GWG, a graphic arts association, ran a survey regarding the use of PDF files in the graphic arts industry. Below are the main issues reported by the 1100 respondents. I’ve included how many people reported seeing each issue.

- The resolution of images is too low(70+%)

Low image resolution leads to a loss of sharpness. When the resolution is really low images get a blocky or ‘pixelated’ look and straight lines that are not perfectly horizontal or vertical will show a staircasing effect. - Use of incorrect or unwanted color spaces (50+%)

Many printers request CMYK files so any PDF file containing RGB or Lab data will be incorrect, even though modern workflow systems and RIPs are perfectly capable of properly processing such color spaces. - Bleed is missing (50+%)

Unless this is corrected a thin white line may appear between the paper edge and close by images or tinted areas. - Fonts are not embedded in the PDF(40+%)

This can lead to text getting printed with a wrong typeface. It can also cause the spacing of characters to be completely wrong, with characters partially overlapping each other while others have too much spacing inbetween them. - There are problems with transparency (30+%)

- The PDF file contains an incorrect number of spot colors (30+%)

Typically printers who ask for pure CMYK files get PDF files with spot colors in them. When spot colors are expected, the same color might appear twice or more, each time with a different name. - There is an issue with overprint (30%)

The inappropriate use of overprint is an issue by itself. In this particular case, we’re talking about there being a difference between the Adobe Acrobat preview (with overprint set to be honored) and the printed result. Issues with overprint can cause page elements to disappear or change color. Small text can become difficult or impossible to read. - Total ink coverage is too high (30%)

This can cause issues on press because the ink can’t dry properly. This can lead to set-off where the ink of a still wet area rubs off on whatever is stacked on top of it. Too much ink can also lead to muddy browns in neutral areas. - Incorrect ICC profiles are used (30%)

The use of incorrect profiles may lead to the colors of the printed result also being incorrect. - The dimensions of the PDF do not match the requested size (30%)

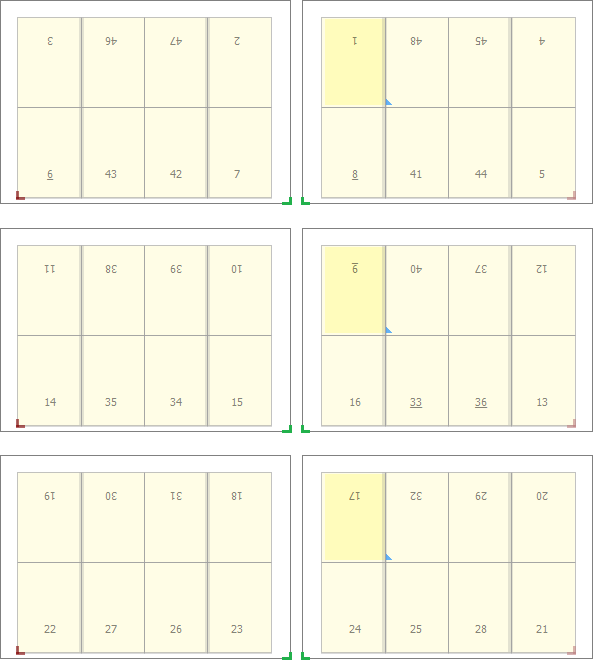

The PDF file format uses so-called page boxes to define page dimensions and bleed. These boxes are used to check if the PDF page size is correct, which sometimes is not the case. A typical example is a business card measuring 85×55 mm positioned in the center of an A4-size page. Obviously the worst problem to receiving a PDF file that has a different aspect ratio. - There are issues with flattened transparency (30%)

Flattening can cause thin white lines to appear. It can cause shifts in color or make text appear fat. Flattening can also cause white rectangles to appear in graphic elements such as artwork or images. - Colors are not reproduced correctly(20+%)

- The output intent is missing or wrong(20+%)

A typical example is the use of a US-specific output intent such as SWOP for files printed in Europe. This can lead to incorrect color separations - The conversion of spot colors to CMYK differs from the expected result(20+%)

- Technical elements are not defined properly (20+%)

A document may need to contain data for die cutting, embossing, spot varnishing or some other type of embellishment. A die line should, for example, be defined as a spot color named ‘dieline’ and set to overprint. If that is not the case, an operator needs to fix this manually or a new PDF file must be requested.

To a lesser extent people also reported issues with corrupted fonts, corrupt PDF files, incorrect CMYK separations, missing objects, RIP errors and incorrect use of layers.

Every item in the previous list, which was published in 2008, is also present in this new overview, indicating that the above issues are unlikely to be resolved in the near future.

How common are PDF issues

The above mentioned GWG survey also asked how often respondents encountered issues with incorrect PDF files.

- 6% claim that over 90% of the PDF files they receive contain errors.

- 17% report that between 50 and 90% of the PDF files contain errors.

- 25% report that between 10 and 50% are troublesome.

- The remaining 52% report less or no errors.

Reasons why PDF files contain errors or are troublesome

One of the reasons why many of these problems go undetected is that designers have the habit of making proofs from their layout, checking those proofs and then creating PDF files. These PDF files don’t get looked at, they are sent straight to the agency or printer. It would be far better if designers created PDF files and then made a proof of these files. This way the consistency between supplied file and proof is much better!

Troubleshooting bad PDF files

Many of the above issues can be fixed with Adobe Acrobat Professional. For some problems having a plugin like Enfocus PitStop may make it easier to troubleshoot the file.

There are a number of prepress workflow systems that also offer built-in tools to correct PDF issues. The preflight engine of the Apogee Prepress workflow of Agfa Graphics is an example of such a solution.

Next to PDF files having some kind of issue, it can, of course, happen that a PDF cannot be ripped or rendered at all. Here are some typical things to try when this happens:

- Use PitStop or another tool to get rid of any irrelevant data in the PDF file. Delete forms, scripts, animations,… and then use ‘Save As’ to create a new clean PDF file.

- Refry the PDF file if you don’t have access to the source file(s).

- If you have access to the source file: clean it up and recreate the PDF: Make sure that any spot colors that are not printed as spots are converted to CMYK in the original file. Delete any unused data (stuff on the pasteboard, elements hidden underneath others, unused pages,… ) You also may want to merge layers, paths or channels. Then do a ‘Save As’ to create a clean source file. Export directly to PDF if the application has an option to do so.

- If the above fail and you have the source files, try recreating the PDF using a different procedure: if the problem file was created by exporting to PDF, try creating a PostScript file and distilling that. If the problem file was created using Distiller or Normalizer, try using ‘Export to PDF’.

- If everything else fails, try opening the PDF in Photoshop and saving it as an image. This operation converts all text to a bitmap so it really has a huge impact on the quality of the output but if everything else fails, this is your last resort.

If you have any question to ask on this article, feel free to comment below and we will respond quick.